Panic buying: why our squirrelling nature kicks in and how we can predict and curb shortages

Panic or over-buying and hoarding of necessities is a common response to crises, especially in developed economies where there is normally an expectation of plentiful supply, a study finds.

It seems we can’t help it when our foraging instincts kick in. However, a UK study has found that we can predict demographically who may be more prone to panic buying and what can be done to alleviate this behaviour to curb shortages in the future.

Photo by cottonbro from Pexels

Global panic buying: it’s a thing now

Long before COVID and the UK HGV driver shortage, our family was exposed to panic buying and crisis-related behaviour. We experienced it during a national drought in Malaysia. The water was cut off for days to homes and businesses through water-controlled zoning.

Buckets of water had to be stored around the house for cooking, bathing and the toilets. Drinking water was bought in bulk before your neighbourhood was scheduled to be cut off. Large rain buckets were installed in gardens just in case it rained, and of course, those ran out of stock, too.

The experience was an eye-opener.

When our family later relocated to hurricane-prone Southern Florida, we experienced panic buying on another level.

One year, when a category 5 hurricane was reported to be coming our way, we had to prepare for no power, house floods, shortages of food, drinking water, toilet paper, and fuel in case of a state evacuation. As I was stocking up for batteries, water and other emergency supplies, I turned my back from my shopping cart only to turn around seconds later to find someone had run off with it.

Even back in the UK, we have all become accustomed to ample supply, whether that is a product, such as power or petrol, or more crucially human resources, such as NHS medical staff, supermarket stackers, farmers and HGV drivers in a post-Brexit and IR35 economy.

Yet panic buying will continue with each crisis and create shortages every time. Given our squirrelling human nature, is there a way to change our hoarding ways in a crisis? A team of researchers seems to think so.

According to a Plos One research study, “panic buying” can lead to temporary shortages. However, there have been few psychological studies of this phenomenon, yet it has been prevalent throughout the animal and human evolution, coined the animal foraging theory.

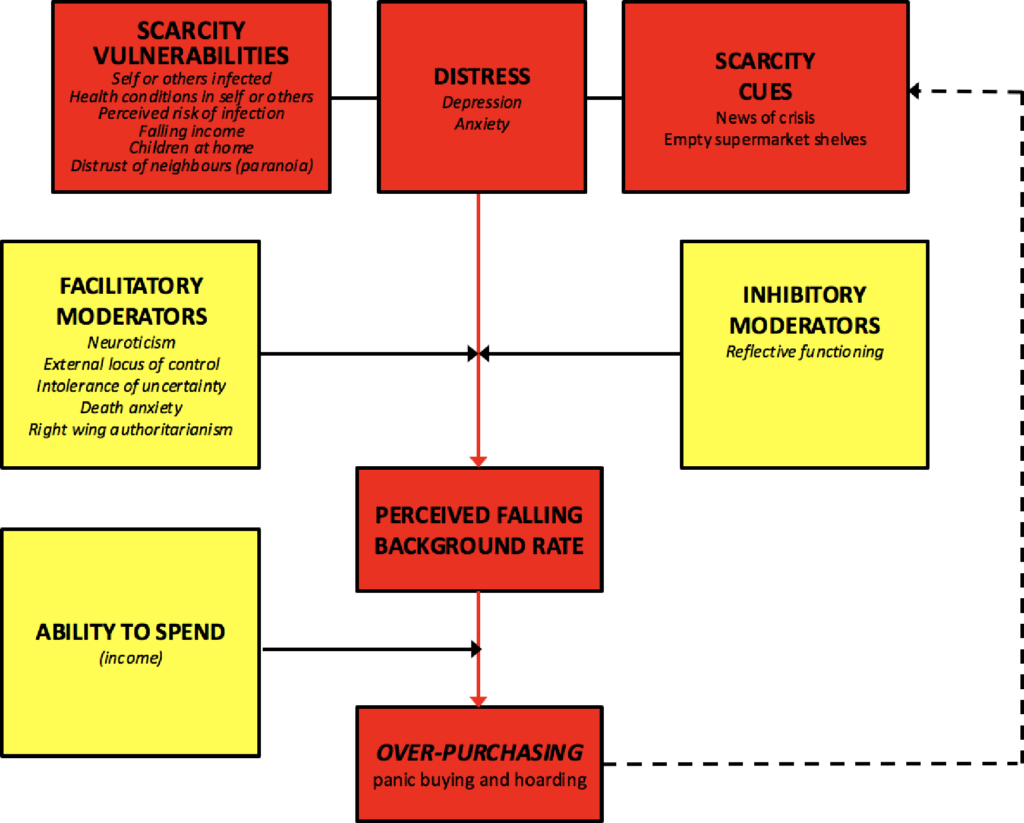

What we do need to learn from panic buying while we are in the midst of one is how to predict them so human resources and supply chains can be proactive. How can the government and any relevant supply chain make predictions about variables that predict over-purchasing by either exacerbating or mitigating the anticipation of future scarcity?

“These variables include additional scarcity cues (e.g. loss of income), distress (e.g. depression), psychological factors that draw attention to these cues (e.g. neuroticism) or to reassuring messages (eg. analytical reasoning) or which facilitate over-purchasing (e.g. income),” said the researchers.

The researchers tested their panic buying model in parallel with nationally representative internet surveys of the adult general population conducted in the United Kingdom (UK: N = 2025) and the Republic of Ireland (RoI: N = 1041) 52 and 31 days after the first confirmed cases of COVID-19 were detected in the UK and RoI, respectively.

About three-quarters of participants reported minimal over-purchasing. That said, there was more over-purchasing in RoI vs UK and in urban vs rural areas.

“When over-purchasing occurred, in both countries it was observed across a wide range of product categories and was accounted for by a single latent factor,” said the report.

It was positively predicted by:

- household income

- the presence of children at home

- psychological distress (depression, death anxiety)

- threat sensitivity (right wing authoritarianism)

- mistrust of others (paranoia)

Analytic reasoning ability had an inhibitory effect. Predictor variables accounted for 36% and 34% of the variance in over-purchasing in the UK and RoI respectively. With some caveats, the data supported the researcher’s model and points to strategies to mitigate over-purchasing in future crises.

Demographics play a large part in panic buying behaviour

With respect to demographic variables, over-purchasing was associated with being younger, female, having children in the home, and having higher income but also with having lost income because of the pandemic. Contrary to expectation, health and infection status of self or others close to the self were not associated with over-purchasing, although a global measure of the perceived risk of infection was. Although distrust of neighbours was not significant in the final model, the more general measure of paranoia was.

Of the psychological distress variables, only depression and death anxiety were significant in the multi-group model, although generalised anxiety and specific anxiety about the coronavirus were significant predictors when zero-order correlations were considered.

Most likely this was a suppression effect caused by including multiple variables that included an anxiety component. This effect may also explain why neuroticism was negatively associated with over-purchasing in the UK in the multi-group model, despite being positively correlated with over-purchasing in both countries. There were also small effects for two of the other personality dimensions–extraversion and low conscientiousness.

“Right-wing authoritarianism was associated with over-purchasing, as expected, but the other psychological variables (the locus of control dimensions, intolerance of uncertainty) mostly failed to contribute to the multi-group model, despite being correlated with over-purchasing in the manner expected. Finally, as predicted, capacity for analytical reasoning (the CRT) was negatively associated with over-purchasing,” said the report.

Panic buying propagated by the press and government

Scarcity cues from the media also play a large part in panic buying. One possible explanation for more panic buying in Northern Ireland than mainland UK comes down to the government of Ireland took decisive action to contain the pandemic sooner than the UK government and, therefore, scarcity cues were more evident in that country when the surveys were conducted.

In support of this, recent research has demonstrated that the timing of Government interventions are associated with panic buying, with earlier interventions coinciding with heightened rates of purchasing behaviours [76]. Commenting on differences between the nations, Irish historian Elaine Doyle was quoted in the UK’s Guardian newspaper [77]:

“While Boris [Johnson, the British Prime Minister] was telling the British people to wash their hands, our Taoiseach was closing the schools. While Cheltenham [a British horseracing festival] was going ahead, and over 250,000 people were gathering in what would have been a massive super-spreader event, Ireland had cancelled St Patrick’s Day,”

Urban over-purchasing exceeds countryside and suburbs

The researchers also found that over-purchasing was more likely to be reported by people living in urban areas compared to those living in suburbs, towns or rural areas. Whilst we did not make a prediction about this, one possible explanation is that scarcity cues (including the visible behaviour of other consumers) are more available in urban environments.

Over-purchasing was also associated with loss of income due to the pandemic, which might at first seem paradoxical, but is clearly consistent with a psychological mechanism by which hoarding is provoked by fear of future scarcity. The number of adults in the household did not predict over-purchasing, but the number of children did, which we predicted on the basis that food-insecurity is a major source of anxiety for parents [42, 43].

How governments and suppliers can alleviate panic buying

The researchers concluded after their research that at a national level, governments, and at a local level, supermarket managers, should anticipate and seek to control over-purchasing by prohibiting bulk-buying, should manage scarcity cues in a way that reduces their salience (for example, by giving careful thought to the way that shelves are stocked), and should facilitate analytical reasoning; in their customers (for example, by providing detailed information about when dwindling stocks will be replaced).

“Our findings point to profiles of individuals who might be particularly vulnerable to over-purchasing, and who could either be reassured by appropriate policies–for example, by providing parents with young children special times when they can shop–or skilfully targeted messaging.,” said the report.

“Forward planning based on our model in preparation for future crises may lead to less panic-buying and less demand-side scarcity, and thereby may reduce the number of problems faced by governments during challenging times,” the researchers proposed.